The view that human life begins at conception is a favoured view of most of the pro-life camp. By it, they do not mean that the sperm and ova were not alive and only became so at conception, but rather that ‘human life’ – in the special sense of a person who deserves protection under the law – begins at conception. Unfortunately for them, this view is logically inconsistent with that pesky thing called reality. There is absolutely no sense in which life, whatever is meant by the term, could be said to commence during the process of conception.

Conception is a process, not a distinct point in time

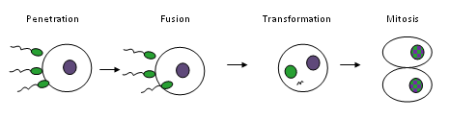

The process of conception, also known as fertilisation, involves many chemical reactions and processes. It is not an instantaneous occurrence. Look at the diagram I made:

So somewhere along that set of chemical reactions, which finally result in two cells with a unique human genetic combination (the zygote immediately after the fusion of sperm has two pronuclei – one from the sperm and one from the ovum), are we to say that a single human life has started? If so, at what point does that happen?

The fact of the matter is that conception is no less of an arbitrary ‘line in the sand’ than any other point that one picks, such as the development of the brain, birth or development of self-awareness. But there is nothing wrong per se with something being arbitrary (after all, the time when people are old enough to vote is arbitrary), so we should now look at whether there is a good reason for not using conception as the start of a human being’s life.

Twins, chimeras and clones

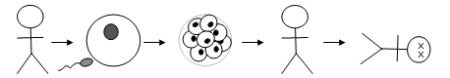

The idea that a “human life begins at conception” also has problems with the existence of identical twins and tetrazygotic chimeras and the possibility human clones. Again, I have diagrams to explain these.

Consider the case of monozygotic twins, as explained by the above diagram. Here we have one fertilisation event, but two individuals result. Do those twins have to share the ‘human life’ they had from conception? Surely not, for we treat twins as separate persons. So, when did both lives start, if not at conception? During the twinning process? Or sometime after? And if lives start during the process of twinning, perhaps it is morally wrong not to twin an embryo, as it prevents the cells from realising their potential as multiple human beings.

Also consider the above diagram of the formation of a tetragametic (four gametes, two sperm + two eggs) chimera. Such an individual results when fraternal twins, derived from separate conceptions, merge very early in development to form a single individual with some cells with one genome and some cells with another (if the two zygotes were different, such as one female and one male or one dark-skinned and the other pale-skinned, this can be noticeable on the person). So, do chimeric people get twice as much human life, seeing as they resulted from two conceptions? Or was a life destroyed when the two embryos merged, despite not a single cell being destroyed? If the intentional formation of chimera is morally wrong, why isn’t the failure to twin an embryo?

Consider finally the case of a human clone (see diagram above), which hasn’t yet occurred but is surely possible. In this case, there is no conception event to be found (unless you go back to the one that created the somatic cell), but yet an individual results. Do clones not have any human life? Surely not, for they would be persons like you or I. So if life begins at conception, how can there be life without conception? Does life begin at conception OR nuclear transfer?

As can be seen, the idea of human life beginning at conception has some serious issues with the processes that can, and sometimes do, occur in human reproduction.

Potentiality

It is often claimed that conception should be the marker for a human life because it marks the formation of something that can grow into a thinking, feeling, reasoning human being. Apart from the fact that conception is not a distinct point, but a process, this potentiality argument has two key problems.

First, if a zygote should be protected because it can from a human being, why not also protect the sperm and eggs, for they can form a zygote which in turn can form a human being. And seeing as males can form billions of sperm but females only form thousands of ova, it follows that males are a million times more worthy of protection than females. But seeing as this conclusion is ludicrous, there must be something wrong with the potentiality argument.

The second, a major flaw, is that being potentially something isn’t the same as being something already. To see this, consider extrapolating the potential argument in the other direction: all human beings will die. And, seeing as a zygote will form a human being who will later form a corpse, it follows that we should treat both people and zygotes as if they were corpses. If we can give the right to life for an unborn baby, maybe we should give the right to a decent burial for a pre-dead corpse (i.e. a live baby). Not to mention that skin cells can replace sperm in forming a human being (see the cloning diagram above), so it follows that each skin cell destroyed is akin to destroying a human being. Unless, of course, having the potential to do something or be something isn’t equal to actually doing or being it.

Member of the human species

Perhaps it could be argued that an embryo should be protected because it is human. We don’t morally protect our own skin cells, despite the fact they are living human skin cells. So, what does the embryo have that skin cells don’t? If the answer is potential to develop into a human being, then this is just the potentiality argument again (and by cloning, perhaps a skin cell does have the potential to develop into a human being).

However, if the answer is that an embryo is a human being (and we accept that as truth, even though it is arguably false) then we need to then ask whether being a human being is enough to give the moral weight – the intrinsic value – conveyed by the term ‘human life’. Perhaps being a human being is only special because it usually correlates with having some other property, such as consciousness or self-awareness, that is special. In that case, then we should be using that other property to value the embryo instead of whether or not the embryo is a human being.

Consider whether it would be acceptable to kill a member of a non-human species that was capable of thinking human-like thoughts, was conscious and felt their lives were valuable, such as the intelligent aliens (think E.T. or Jar Jar Binks) or robots of science-fiction. If such a species (biological or not) is also worthy of protection, due to the fact they have certain psychological characteristics, then isn’t it safe to say that is those characteristics that are truly being valued here?

In addition, applying rights based on what group you belong to, rather than what you are able to do, seems a lot like bigotry or prejudice. History shows us many applications of rights based on being of a certain economic class, race, gender or religious group. Why should doing the same for being part of a species be any different?

Unique genetic combination

It is often said that because the zygote is a new human being because it has a unique human genome. This is a relatively weak argument, because a unique genome is not required to form a human being (e.g. identical twins, or clones, or human parthenotes) and unique genomes often do not form human beings (e.g. mutated genomes of cancers or the modified genome of induced pluripotent stem cells). Unless we are willing to admit that melanomas are actually human beings because they have a different genome, and that a woman who is pregnant with her clone (or identical twin) is not actually pregnant with a human being, then this argument should be abandoned.

Failure of an embryo to implant

The fact that only a fraction of zygotes go on to form a human being also hits hard the “life begins at conception” dogma. Firstly, the results of most conceptions are not viable embryos, and these abnormal embryos are usually passed out during a menstrual cycle. If such embryos are human beings, should we hold a funeral? Should we feel bad for not even realising they existed in the first place? Also, assisted reproductive technologies are much like natural reproduction in that far more embryos are conceived than result in pregnancy, and therefore shouldn’t IVF and sex be just as much of a problem as abortion? Or is the death of dozens of lives justified if it creates a life in the process (if that is the case, shouldn’t doctors and nurses be making babies instead of saving lives)?

Further, the oral contraceptive pill is known to make the uterine environment more hostile to any embryos that would implant there. The hormone progesterone released during breastfeeding acts in the same was as the oral contraceptive pill (in fact, progesterone analogues are the key ingredient of the pill), which is why breast-feeding is a ‘natural contraceptive’. Therefore, shouldn’t both the contraceptive pill and sex while breast-feeding be complained about just as much as abortion and embryonic stem cell research?

Conclusion

It is evident that the idea that life begins at conception is at odds with reality. Many human beings can result from a single conception, many conceptions can result in just one human being and theoretically human beings could develop without any conception event occurring at all. The idea that conception is a key point in the process of development is unfounded, as the potential to develop into a human being is not only possessed by sperm and eggs, but is completely logically fallacious in the first place. In addition, it doesn’t even appear that being a human being qualifies as having the intrinsic value required to convey moral status, as it is possible that non-human beings should have same intrinsic value attributed to ‘human life’. Neither can genetics rescue this argument, for a unique genetic composition is possessed by some non-human beings, and some human beings don’t have a unique genetic composition. Finally, the way most people act normally, and the way nature is, is very wasteful of zygotes, making the conclusions of this argument very difficult in practice.

It is not a scientific fact that human life begins at conception. The truth is that human life, in the sense of a person like you or I, emerges slowly from the genetic information and molecules that made up the sperm and eggs in your parents body, from the processes of controlled growth of the resulting embryo and foetus, using nutrients that nourished you in the womb. Science informs us that it is a continuous process. Those looking for a nice distinct point in time that can be used as the starting point of each person’s existence will be sorely disappointed if they look at the science. Philosophically, I’d argue that no intrinsic value of human beings exists, except for the value applied by a being to itself. Although this may be criticised for being overly restrictive (not attributing any intrinsic value to neonates), this criticism only works if we have a another significant reason to think neonates should have such value – I do not believe such a reason exists (see also the latter part of this post).